July 19, 2024 at 11:00 PM GMT

Two months had passed since a devastating cyberattack impacted hospitals and clinics in southeast London. Doctors like Delaney, who also teaches at Imperial College London, were finally experiencing a semblance of normalcy. They could once again send off urgent blood tests, and cybersecurity experts were steadily repairing and replacing the IT systems previously shut down by a criminal hacker gang.

However, as he entered the clinic, he noticed the receptionist hurriedly gathering paper notepads and searching for a business continuity plan. The system that doctors across England rely on to view patient records had suddenly stopped working.

This time, the culprit was not a ransomware gang but a company meant to protect against such threats. CrowdStrike Holdings Inc., one of the largest cybersecurity software makers, had released a flawed update, causing a global IT meltdown that crippled airports, banks, stock exchanges, and businesses worldwide.

The Microsoft Corp. Windows Recovery screen displayed at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York on July 19.Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg

Incredibly, a tiny file—just big enough to hold a single web page image—was responsible for the world’s biggest IT outage, experts say. This file, named “C-00000291*.sys,” was hidden in an update for CrowdStrike’s Falcon sensor product. The faulty file caused an error in Microsoft Corp.’s Windows operating system, rendering computers inoperable and triggering the infamous “blue screen of death.”

The incident exposed the fragility of the global IT system on an unprecedented scale and highlighted the dangers of heavy reliance on a few tech giants. If one of these companies experiences an outage or gets hacked, the impact can ripple across the global economy. Microsoft dominates the personal computing market with its Windows operating system, while CrowdStrike is a major cybersecurity provider for thousands of organizations.

After Microsoft, CrowdStrike is the second-largest maker of “modern endpoint protection” software, controlling 18% of the $12.6 billion market, according to research firm IDC. The Austin-based company serves 29,000 organizations worldwide, meaning the outage likely affected millions of computers that could take weeks or longer to fix because they must be repaired manually.

“It’s a real mess,” said Saif Abed, a former NHS doctor and cybersecurity expert. “CrowdStrike has affected Microsoft, and the entire NHS is reliant on Microsoft. It’s a domino effect of potential failings.”

As the outages spread from Asia and Australia across Europe and to the US on Friday, George Kurtz, CrowdStrike’s co-founder and CEO, apologized for the error. “This is not a security incident or cyberattack,” he said. “The issue has been identified, isolated, and a fix has been deployed.”

Kurtz didn’t specify how the flaw got into the update. Critics argue that CrowdStrike and other cybersecurity companies have sacrificed basic security principles while chasing profits and trying to appease shareholders.

“It’s time for the industry to grow up and maybe slow down a bit,” said Federico “Fede” Charosky, founder and CEO of Edinburgh-based security services firm Quorum Cyber. “Some developer somewhere made a change and there was no analysis of what impact that change would have. There’s clearly a lack of quality assurance and testing and taking shortcuts in pursuit of speed. What this shows is that we’re delusional in our complete trust in the technologies that are so intrinsic to running everything.”

While such incidents are exceedingly rare, Kurtz has experienced a similar situation before. In 2010, as the CTO of McAfee, he dealt with an update that mistakenly labeled a legitimate Windows file as infected, paralyzing computers globally. The flawed update was pulled just 16 minutes later, but the damage was done.

Cyber industry observers wonder if CrowdStrike will learn from its own mistake. Some argue the company has been inviting trouble. For years, CrowdStrike has criticized Microsoft for its security lapses, using those shortcomings as a selling point for its own products.

Shortly after the US government released a report criticizing Microsoft for a “cascade of security failures,” Kurtz cited the findings to investors, saying Microsoft’s issues prompted an “outpouring of requests” from potential customers. “There’s a widespread crisis of confidence among security and IT teams within the Microsoft security customer base,” he said.

“CrowdStrike has tried to bash Microsoft as much as they could and they were trying to profit from it,” Charosky said. “But nobody escapes when your company is such a massive part of the world’s infrastructure. This is karma. When a company graduates from being a startup to being critical national infrastructure, it needs to behave differently, and I don’t know if CrowdStrike has gone through that transition.”

Some online commentators have dubbed CrowdStrike’s flawed update the “malware of the year,” owing to the level of destruction it has caused. The recovery time for affected organizations could be weeks or longer, similar to the time it takes to rebuild a network after a ransomware attack.

The biggest challenge in restoring the computers is that CrowdStrike’s fix needs to be applied manually, computer by computer, by someone with administrative privileges—an exceptionally time-consuming process, especially in an era of remote work.

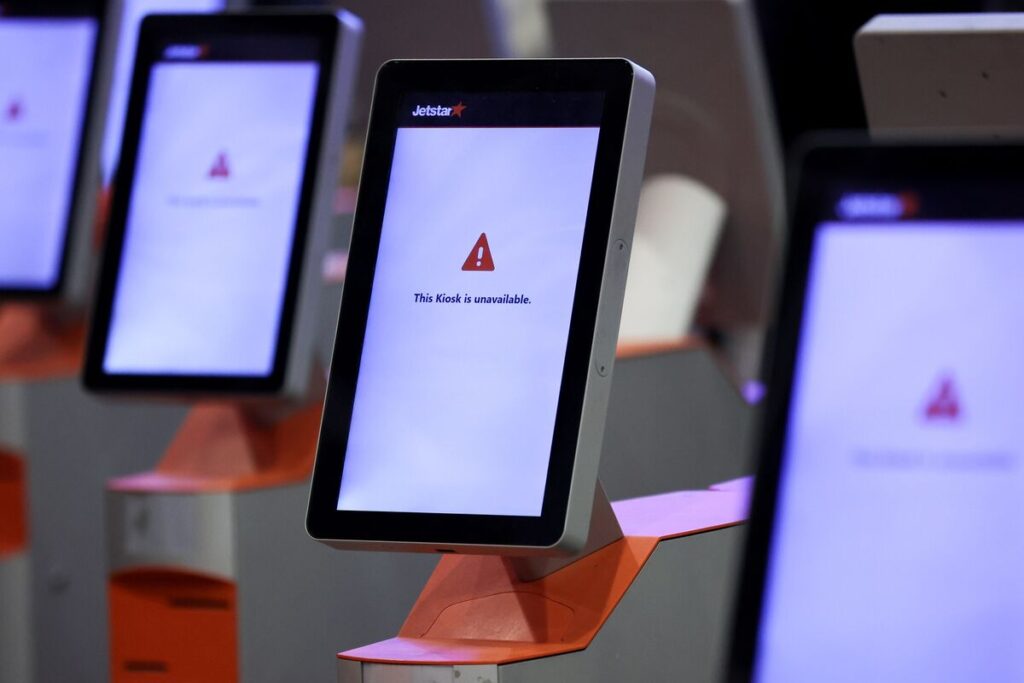

A self check-in kiosk at Jetstar Airways’ check-in area at Sydney Airport on July 19.Photographer: Brendon Thorne/Bloomberg

Michael Henry, co-founder and chairman of Plano, Texas-based cybersecurity firm Accelerynt Inc., shared that a large US retailer client had to mobilize its entire IT staff to work around the clock, manually updating approximately 6,000 affected computers. The retailer anticipated it would take the entire weekend to restore critical systems and up to three weeks to fully bring all systems back online.

“It’s crazy. They’re triaging, focusing on critical systems first,” Henry said. “It’s a retail operation, so they’re prioritizing getting the stores back up.”

Henry, like many others, is left questioning how such a massive outage occurred.

“CrowdStrike has done more to disrupt global business than all the ransomware operators combined,” he said. “This incident highlights the enormous risk we carry with the very software we rely on for protection: if these companies make a mistake, it can take your business down.”

An error message on a screen at a Starbucks in Austin, Texas on July 19.Photographer: Jordan Vonderhaar/Bloomberg

Cybersecurity and legal experts predict CrowdStrike will likely face lawsuits, financial costs, and other penalties. The incident is also expected to reignite discussions about the increasing concentration of power—and risk—among a few cybersecurity companies.

By Silicon Valley standards, the cybersecurity industry is relatively young. It emerged during the era of worms and floppy-disk viruses, and two decades ago, it was dominated by Symantec and McAfee. These companies focused on a now-quaint strategy of writing “signatures” to block known malware strains.

Travelers wait at Berlin Brandenburg Airport in Germany, on July 19. Photographer: Liesa Johannssen/Bloomberg

The challenge is that these technologies are predominantly controlled by Microsoft and CrowdStrike. Justin Cappos, a computer science professor at New York University, has been vocal about the dangers of consolidation in the security industry. He argues that centralized decision-making can lead to significant problems, a concern echoed in other areas of tech.

“Big companies make big mistakes in the tech space,” he said in an interview. “A lot of the really bad security designs we’ve seen have come out of efforts by major companies.”