December 24, 2024

Vietnam’s Booming Consumer Class Embraces Luxury and Modern Living

TOKYO — Nguyen Thi Huyen, a married mother of two from Hanoi, recently joined the ranks of Vietnam’s growing upper middle class by purchasing her family’s first apartment from Vinhomes, part of the country’s largest conglomerate, Vingroup.

“Buying a house is a trend among our generation. Real estate prices in Vietnam are soaring, so buying a house means having an asset to sell,” she shared with Nikkei Asia. According to Batdongsan.com, a prominent Vietnamese real estate platform, average home prices nationwide rose by 24% between January 2023 and June 2024, with Hanoi’s apartment market leading the charge.

This spending spree isn’t limited to real estate. Vietnam’s rapidly growing economy and rising incomes have transformed formerly unattainable luxuries—like cars, air conditioners, luxury smartphones, and high-end cosmetics—into mainstream purchases for an increasingly affluent population.

“Until my parents’ generation, being poor was the norm, and frugality was necessary,” explained 38-year-old translator Nguyen Kim Ngoc, who lives in Hanoi. “Today, the desire for high living standards is stronger than ever. People no longer hesitate to display their wealth. During our parents’ and grandparents’ time, wealth was hidden to avoid scrutiny from the authorities.”

From Poverty to Prosperity

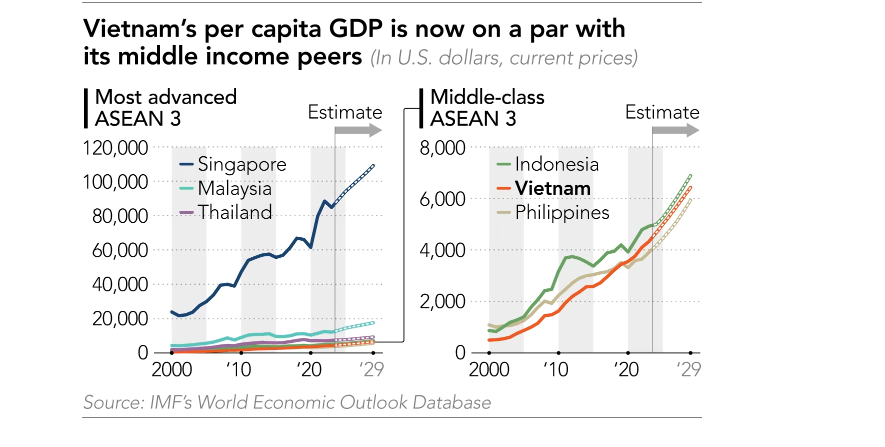

Vietnam’s economic transformation is remarkable. In 1990, the country’s per capita GDP was just $122, a fraction of Thailand’s, the Philippines’, and Indonesia’s. Decades of economic liberalization and foreign investment have propelled Vietnam’s per capita GDP past $3,000 by 2018, surpassing the Philippines and closing in on Indonesia by 2024.

Real Estate: The Ultimate Status Symbol

Despite a construction slowdown caused by financial strain on developers and a sweeping corruption crackdown, property remains the most coveted asset. Real estate company Savills reports that only 33,500 new condos were built in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City in the first half of 2024, fewer than in 2014. Yet demand remains robust. Vinhomes recorded contracted sales of 51.7 trillion dong ($2 billion) during the same period, a 27.3% increase year-over-year.

Cars Signal Consumer Confidence

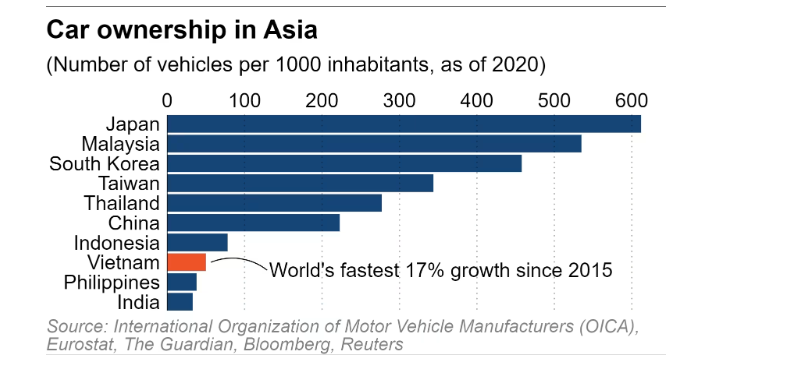

Car ownership is another indicator of Vietnam’s growing consumer power. As of late 2023, there were 63 cars per 1,000 people, nearly triple the ratio from 13 years earlier, according to trade ministry data. While Vietnam lags behind Indonesia in overall car ownership, it has the fastest growth rate in the world, averaging 17% annually from 2015 to 2020, according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers.

In the July-September 2024 quarter, auto sales reached 90,701 units, a 25% year-on-year increase, marking the highest growth rate in the region. Projections suggest annual vehicle sales could hit 1 million by 2030.

A Rising Consumer Powerhouse

Vietnam’s surging economy has reshaped cultural and economic norms, with its growing consumer class leading a shift toward modern living. From real estate to luxury goods, this Southeast Asian nation’s booming spending power is cementing its place as one of the region’s most dynamic markets.

Vietnam’s Nasdaq-listed electric vehicle maker VinFast, while not yet reflected in the country’s official statistics due to its disclosure policy, reported selling 44,773 EVs in the first nine months of 2024.

“In a nation where motorbikes dominate and car ownership is viewed as a symbol of success, the spending power of the upper middle class is poised to grow even further,” remarked a Hanoi-based representative from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), a government aid organization.

Tran Nguyen Vu, a 33-year-old IT engineer, exemplifies this rising trend. In October, he purchased a Japanese Subaru for 1.13 billion dong, adding to his earlier investment in a Vinhomes apartment in Hanoi’s city center—a two-bedroom home he acquired for 1.85 billion dong two years ago.

“I’m not one to splurge on luxury brands or high-end appliances,” Vu shared with Nikkei. “But I do believe in spending on things that genuinely enhance happiness and quality of life.”

In addition to apartments and cars, smartphone sales in Vietnam are experiencing rapid growth. With an estimated 85.73 million registered smartphones among the country’s 100 million residents, this figure represents a 6.9% increase from the previous year—double the number in 2020 and 23 times higher than in 2014, according to data from Statista.

Vietnam’s surging economic output and rising investments are key drivers behind the growing ownership of items once considered luxuries. However, cultural factors also play a significant role in this trend.

One such factor is the prevalence of multigenerational households. As highlighted by the Vietnamese consulate in New York, it is common for three or four generations to live under one roof, rooted in traditional values that see “more children, more fortunes” as a blessing.

Nguyen Thu Ha, 27, who currently works in Japan, recalled her family’s experience of multigenerational living. From 1997 to 2011, three generations of her family, totaling 13 people—including uncles, aunts, and other relatives—shared a home on the outskirts of Hanoi. “This type of living arrangement is still common in Vietnam,” she told Nikkei.

Her grandparents own the house, so her parents and relatives avoid paying rent. All family members contribute equally to shared expenses, such as electricity and water.

“There were times when the house felt crowded, but the benefits of sharing household chores and supporting each other are significant. We can also use the savings from rent to invest in education and entertainment,” she explained.

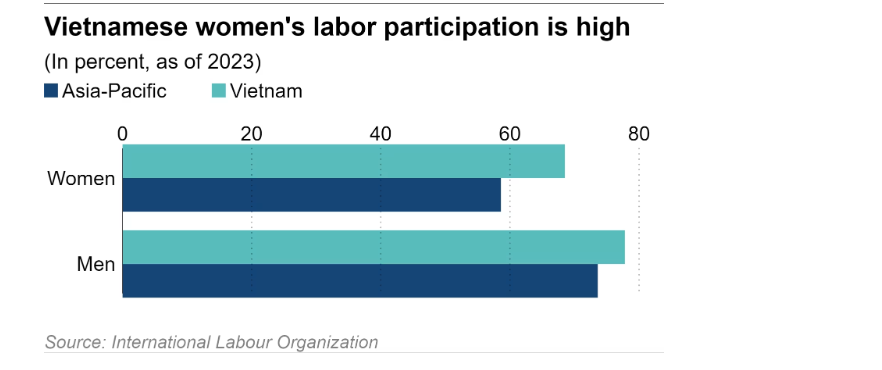

Another cultural factor driving spending power in Vietnam is the prevalence of dual-income households. According to estimates from the International Labour Organization, Vietnam’s male and female labor force participation rates were 77.8% and 68.5% last year, compared to regional averages of 73.6% for men and 58.6% for women in East Asia and the Pacific.

“In my experience, women in Vietnam are exceptionally hardworking, and the number of female managers is steadily increasing,” noted the manager of a Japanese company in Ho Chi Minh City. “It’s a more supportive environment for women to work compared to Japan or many other Southeast Asian countries.”

Vietnam’s declining fertility rate, especially since the 1990s, has also boosted discretionary spending as the economy expands. In 1990, the country’s fertility rate stood at 3.6 children per couple, but by 2022, it had dropped to 1.9—the fourth lowest among major ASEAN economies, after Singapore’s 1, Thailand’s 1.3, and Malaysia’s 1.8. This shift has allowed families to allocate more resources to luxurious goods and services.

Vietnam’s stable domestic politics, affordable labor costs, and relatively low land prices have made it a prime destination for foreign investment for over a decade. Its proximity to China, deep-water ports in the north and south, and robust land connectivity across the Indochina Peninsula provide a strategic advantage. Additionally, the U.S.-China rivalry has positioned Vietnam as a secure and appealing alternative for investors.

Major sources of foreign direct investment (FDI), such as South Korea, Japan, Singapore, and the U.S., are not only establishing production bases in Vietnam but are also recognizing the country’s potential as a lucrative consumer market.

Japanese companies, in particular, are ramping up their investments to tap into Vietnam’s growing upper middle class. Takashimaya, a leading department store operator, plans to develop a commercial and office complex in Hanoi by 2027, building on the success of its store in Ho Chi Minh City, which opened in 2016.

Real estate giant Mitsubishi Estate has launched four projects this year, including large-scale apartment complexes, bringing its total investment in Vietnam to $500 million, according to NNA, a Japanese news outlet focused on Southeast Asia.

Cosmetics manufacturers such as Shiseido and Daiichi Sankyo Healthcare are also eyeing the Vietnamese market, partly due to economic challenges in China, which had been their primary focus.

Nguyen Kim Ngoc, the Hanoi-based translator, predicts the economic boom will persist as Western consumer ideals increasingly influence Vietnam’s upper middle class. “People here have never had so much money or so many opportunities to spend it and showcase their wealth,” she observed, highlighting the shift in spending habits and aspirations.