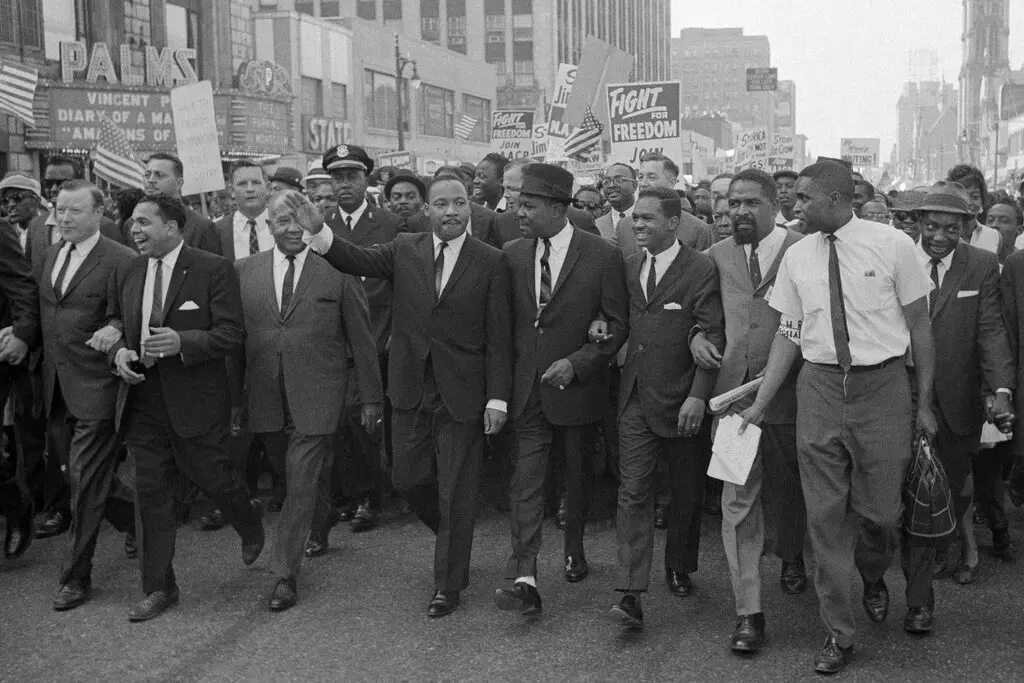

Nearly 56 years after his death, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. remains distinct among 20th-century civil rights leaders. He was the most prominent, frequently appearing on television, and his innovative approach to combating American apartheid set him apart. King’s influence was so significant that it fueled the paranoia of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who feared the emergence of a Black messiah capable of inciting a revolution among the oppressed Black masses in the nation.

However, King was far from a solitary messiah. Initiating his activism at a young age, organizing the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott at just 26, he built a movement more collaboratively than history often acknowledges.

Medgar Evers, inspired by King, alongside Malcolm X, formed what James Baldwin termed the great trio of the civil rights movement. The connection between Evers and King, often lost in history, reveals the challenges the movement faced in balancing the interests of Black Americans in cities with those of rural sharecroppers, donors, competing civil rights groups, and politicians in Washington.

Evers, the then-32-year-old Mississippi field secretary for the N.A.A.C.P., wrote to King in 1956, aiming to bring him to Mississippi. Evers, a World War II veteran, had returned with a determination to fight for “first-class citizenship” for Black Americans. Although working for different organizations, Evers and King shared a vision of liberation, with Evers advocating King’s Montgomery boycott as a model for engaging the terrorized sharecroppers in Mississippi.

Despite differences and criticism from their respective organizations, Evers and King met in 1957, marking the beginning of a correspondence, affinity, and mutual admiration that lasted until their deaths.

Evers, who continued correspondence with King despite opposition from the N.A.A.C.P., had a more radical vision for Black liberation than his New York-based bosses. He viewed King’s methods as aligned with his vision of empowering Southern Black communities to stand up for themselves.

As the civil rights movement gained momentum, the federal government, especially the Kennedy administration and the FBI, grew concerned about its potential to unite activists across racial lines. This fear was realized during the first wave of Freedom Rides in 1961, highlighting the collaboration between various civil rights organizations.

In 1962, the N.A.A.C.P., the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress of Racial Equality formally united, forming the Council of Federated Organizations. Despite opposition from the N.A.A.C.P., Evers continued to correspond with and seek collaboration with King, using King’s strategies to build a successful boycott movement in Jackson, Mississippi.

After Evers’s assassination in 1963, his widow, Myrlie Evers, carried on his legacy. The friendship between Coretta Scott King, Myrlie Evers, and the widows of Malcolm X formed a sisterhood of widows.

King’s legacy and transformative changes in civil rights, voting rights, and various social justice movements were built by coalitions, not individuals. Celebrating King’s achievements requires acknowledging the collaborative efforts of many individuals, such as Medgar Evers, who worked together to bring about lasting change.