Archaeologists are rapidly adopting advanced ground-scanning technology to uncover and preserve hidden ancient civilizations before they are lost forever.

In the heart of Siena, Italy, stands a cathedral that has been a testament to history for nearly 800 years. This architectural marvel, visited by millions, is known to most as “the cathedral.” However, Stefano Campana, a seasoned archaeologist at the University of Siena, sees it differently: he calls it “the church that is visible now.”

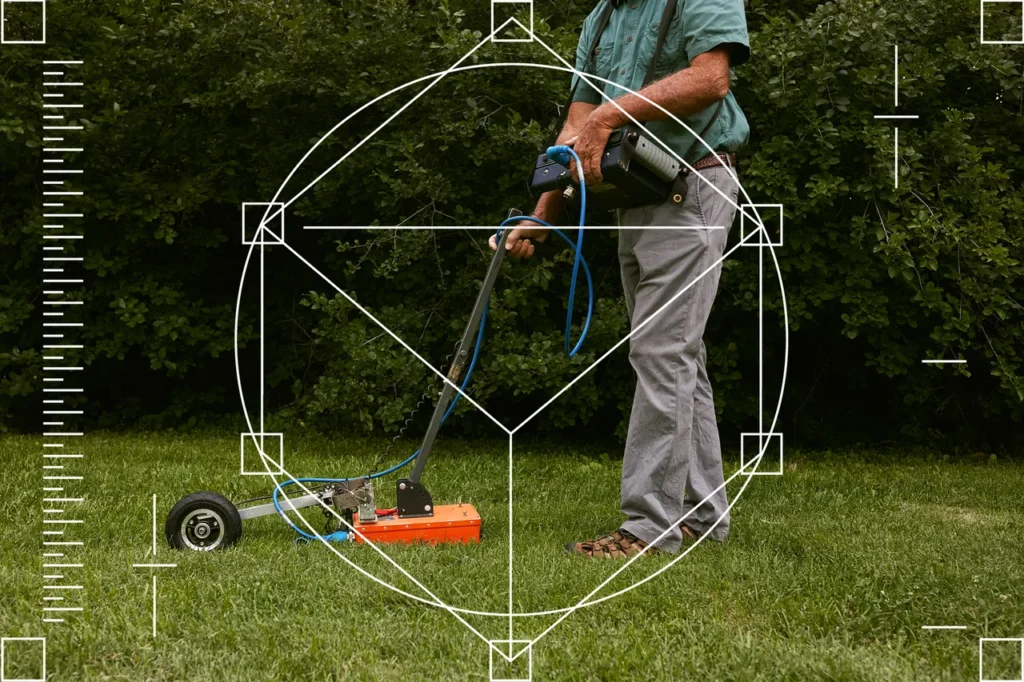

Campana’s approach to archaeology goes beyond traditional excavations. He employs advanced electromagnetic equipment, such as ground-penetrating radar, to peer into the past. This technology transmits high-frequency waves into the earth, detecting subsurface anomalies indicative of architectural structures.

In 2020, during the Covid lockdown, Campana and his team were granted permission to survey the cathedral’s interior. Utilizing instruments designed for glaciers and mines, they scanned the floors, uncovering evidence of structures from nearly 1,200 years ago.

Inspired by their findings, Campana pondered the possibilities of this technology. He envisioned scanning the entirety of Siena, uncovering the hidden history beneath its streets and squares. Partnering with Geostudi Astier, he initiated the Sotto Siena (Under Siena) project, aiming to document Siena’s archaeological heritage before it succumbs to modern development.

Campana’s vision is a journey through overlapping worlds, where radar reveals ancient foundations beneath bustling streets and Etruscan ruins beneath corner shops. The Sotto Siena project has already uncovered evidence of 15th-century pavilions in the Piazza del Campo.

The team’s city-scanning setup includes an electric utility vehicle equipped with radar equipment and a Wi-Fi antenna to relay data. Despite technical glitches and curious onlookers, the team persevered, conducting surveys into the night, uncovering pipelines, historic masonry, and remnants of long-gone structures.

This endeavor represents a shift in archaeological methods towards more sophisticated and non-invasive techniques, preserving historical sites while uncovering their secrets. The success of the Sotto Siena project has inspired archaeologists to dream bigger, envisioning the uncovering of entire ancient landscapes, like the Roman city of Carnuntum, through electromagnetic data.

Back in 2000, Immo Trinks, then a graduate student, was part of a groundbreaking achievement in archaeology at Carnuntum. Serving as an assistant, he contributed to mapping nearly 15 acres in a single day using magnetometry, a technique that detects minute differences in magnetic field strength between structures and the surrounding soil. This accomplishment marked what could be termed a land-speed record for archaeology.

Since that pioneering endeavor, Trinks has been an integral member of a diverse group of international geophysicists, all dedicated to revolutionizing the field of modern archaeology. He has shared his extensive knowledge and passion for the field as a teacher at the University of Vienna and, until recently, as the deputy director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology, also known as LBI ArchPro.

Trinks is not only recognized for his immense ambition and comprehensive knowledge of his field but also for his meticulous attention to the technical details that are crucial for the success of large-scale archaeological projects. His nerdy obsession with these details ensures that ambitious undertakings are executed effectively and yield the desired outcomes.

Immo Trinks and Alois Hinterleitner take radar scans in Carnuntum, a ruined Roman city outside modern-day Vienna. PHOTOGRAPH: MICHAELA NAGYIDAIOVÁ

Immo Trinks and Alois Hinterleitner take radar scans in Carnuntum, a ruined Roman city outside modern-day Vienna. PHOTOGRAPH: MICHAELA NAGYIDAIOVÁ

For the 50-year-old Trinks, employing electromagnetic tools to document and preserve humanity’s history is more than a job; it’s a moral obligation. He highlighted that globally, invaluable archaeological sites are vanishing under the unstoppable wave of urbanization, economic development, climate change, and armed conflict. In Europe alone, unexplored Roman towns have been buried under supermarkets and large retail stores. Across the world, undiscovered Stone Age villages have been obliterated by highways, airports, and expansive agriculture. With each passing year, more of our collective heritage slips away.

However, with the advent of technology enabling entire landscapes to be mapped within days using off-road vehicles, and the data being processed almost instantly with the help of feature-recognition algorithms and image-processing software, a promising prospect emerges. We might be standing on the threshold of creating a comprehensive map of all archaeological sites across the globe.

Trinks passionately conveyed, “We want to map it all—that’s the message.” He emphasized that the goal is not just to map a Roman villa or an individual building, but to map entire cities and landscapes, and even beyond. Trinks is serious about this vision. In the summer of 2022, he penned a manifesto advocating for the establishment of an International Subsurface Exploration Agency. This agency would initially aim to scan every mappable square meter of land in Europe, extending its reach to the bottoms of lake beds.

Trinks adjusts a satellite receiver during fieldwork in Carnuntum. PHOTOGRAPH: MICHAELA NAGYIDAIOVÁ

“Consider the European Space Agency,” Trinks remarked as we dined near the Danube River, which flowed just beyond a ridge from the ancient Roman city. The ESA costs each European taxpayer merely about €15 a year. “Fifteen euros is the cost of a decent pizza and a beer,” Trinks noted. “I’m willing to forgo a beer and a pizza annually to have thousands of individuals exploring downward instead of upward.” He cautioned that if we neglect this, “our grandchildren will question us: Why didn’t you do more to document what remained? Because they won’t have the opportunity once it’s lost.”

Trinks’ ambitious vision necessitates not just the hardware capable of scanning an entire continent, but also the software to interpret the vast amount of data generated. One morning at the University of Vienna, Trinks introduced me to Alois Hinterleitner, whom he dubbed a “magician.” Hinterleitner, a software engineer with GeoSphere Austria and a partner of LBI ArchPro, is Austrian and a passionate mountaineer. Trinks humorously remarked that a vast amount of geophysical survey data would be left in limbo if anything were to befall Hinterleitner during his adventurous expeditions. He is so pivotal to the project that Trinks coined the term “Aloisify the data” to describe making the data archaeologically comprehensible.

Over refreshments, Hinterleitner guided me through the software he employs, which enables him to filter radar results based on various signal properties. A feature named Remove Stripes was developed to eliminate inconsistencies in the data set, caused by alterations in the measuring instruments or diverse scanning techniques. These modifications can result in bright lines—stripes—appearing in the scan. The filter, while effective, can also unintentionally remove traces of walls or foundations, including distinctive features of Roman architecture, which can mimic stripes. In essence, there’s a risk of inadvertently erasing the very elements you are seeking.

Hinterleitner showcased images from several expeditions to the island of Björkö, Sweden, conducted between 2008 and 2012. The manufacturers of Trinks’ radar equipment had advised against scanning a large meadow on the island, deeming the data unmanageable and the results uninterpretable. “They even used the term forbidden,” Trinks recalled with a chuckle. “But that didn’t deter me, because we had Alois.”

Employing towed radar equipment, Trinks and his team managed to scan not just the main meadow of Björkö but the entire island. The data was processed, filtered, and converted into images in a mere three weeks. While Björkö was already recognized for housing over 3,000 Viking graves, Trinks’ survey depicted those tombs—with no visible surface features—in such detail that the outline of a coffin became discernible. “We may not be able to see the horns on the helmet yet,” Trinks shared, “but, for the first time, we can discern there is something inside the coffin.”

A researcher from GeoSphere Austria drives a ground-penetrating radar system around the organization’s garden in Vienna. PHOTOGRAPH: MICHAELA NAGYIDAIOVÁ

The utilization of big data in archaeology has sparked debates within the field. When LBI ArchPro received its initial funding over a decade ago, Trinks shared that some younger scholars felt alienated by what they saw as an emphasis on advanced technology at the expense of long-term institutional objectives, such as hiring full-time staff or providing stipends to graduate researchers. Even those who advocate for geophysical tools warn that the sheer volume of data collected can overshadow interpretive rigor. With a plethora of anomalies to investigate, discerning which ones are genuine becomes a challenge.

Lawrence B. Conyers, a prominent critic, is widely regarded as one of the leading experts in the application of ground-penetrating radar in archaeology. He has authored several seminal books on the topic and has conducted surveys worldwide, exploring lost villages in Costa Rica to ancient Roman ports submerged in Portuguese marshes. While Trinks and his team operate high-end machinery across historically significant landscapes at considerable speeds, Conyers conducts his surveys more modestly, often in sandals. He typically brings his radar unit, which he carries as hand luggage, telling airport security it’s a device for examining inside walls. “Avoid mentioning the word radar,” he recommended, noting that it could trigger concerns.

I had the opportunity to meet Conyers on the island of Brać, located off the coast of Croatia, at the site of an ancient hill fort. He was there to collaborate with an international group of archaeologists and historians seeking evidence of pre-Hellenistic settlement and trade, dating back to the Bronze Age. The picturesque blue waters of the Adriatic Sea were visible to the west, and a vast gorge extended into the island’s interior. The landscape was dotted with wild asparagus growing in tangled bunches.

A researcher from GeoSphere Austria drives a ground-penetrating radar system around the organization’s garden in Vienna. PHOTOGRAPH: MICHAELA NAGYIDAIOVÁ

Amidst a light drizzle on the island of Brać, Lawrence B. Conyers, a specialist in ground-penetrating radar, maneuvered his equipment across the landscape, unveiling fascinating subterranean structures. The thrill of uncovering unseen architectural forms was evident, with each step suggesting the presence of concealed rooms, passageways, or courtyards.

Conyers, enjoying financial independence and known for his informal and bold demeanor, presented a stark contrast to his European peer, Immo Trinks. He questioned the dependence on sophisticated equipment to address archaeological challenges and championed a more reflective approach to interpreting the ground as a medium for transmission and understanding the interactions of radar energy within it.

This viewpoint underscored the constraints of radar technology, highlighting the possibility of some subterranean objects remaining undetected and the risk of the nascent field of high-speed electromagnetic archaeology being overshadowed by its technological aspirations. Both Conyers and Stefano Campana emphasized the necessity of integrating electromagnetic surveys with actual excavations to confirm discoveries.

At a meeting in Croatia, Conyers disclosed that the preliminary interpretations of the data had been erroneous, with what were thought to be architectural features actually being disturbances from a nearby cell tower. This revelation accentuated the complexities and potential pitfalls of interpretation in archaeological investigations.

In her book “The Ruins Lesson,” Susan Stewart asserts that it is preservation, not decay, that is the anomaly. Nonetheless, the advent of geophysical instruments is altering this narrative, demonstrating that even the most fleeting human presence leaves an imprint. The process of democratizing history is in progress, with geophysics revealing the existence of ordinary individuals and previously neglected cultures and periods.

The envisioned global International Subsurface Exploration Agency, as suggested by Trinks, holds the promise of substantially expanding our comprehension of human history. Before leaving Vienna, Alois Hinterleitner showcased the revolutionary capabilities of geophysics, illustrating how vanished cities and their intricate features could be brought to light through radar surveys, suggesting a future where the entire surface of the Earth could serve as a window to our past.

This journey into the concealed strata of human history, backed by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, illuminates the dynamic field of archaeological study and the significant influence of geophysical instruments in revealing the remnants of our existence.