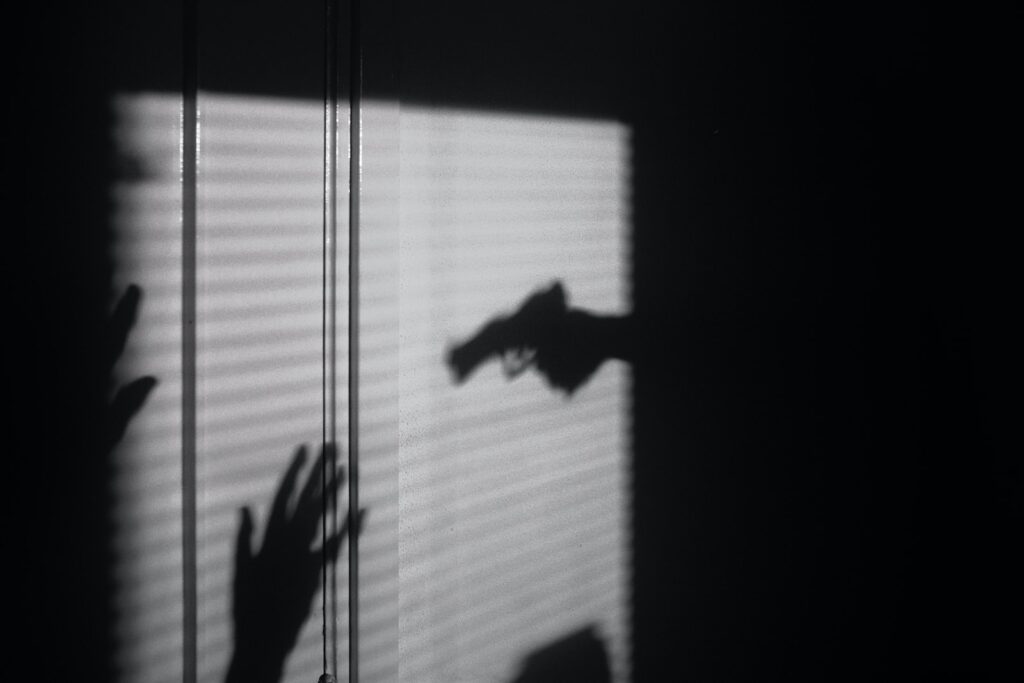

The assassination of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, an advocate for Sikh separatism, in Canada this past June, has ignited a fiery dispute between Canada and India, highlighting a volatile element of the evolving global disorder: state-sponsored assassinations. The elimination of political dissidents, terrorists, and significant political or military figures is a practice as ancient as politics itself, but there is a growing indication that its frequency is on the rise. Both Ukraine and Russia are actively pursuing each other’s leaders. Beyond the European conflict, emerging powers like Saudi Arabia and India are asserting their influence abroad and expressing their resentment towards perceived Western hypocrisy regarding state-sponsored assassinations. Advancements in technology, including sophisticated drones, have made it increasingly convenient for governments to execute individuals with pinpoint accuracy from afar.

However, even as assassinations become more accessible and potentially more commonplace, the ethical and legal considerations surrounding them remain complex and unclear. The Western response to such killings is a testament to this ambiguity. The murder of Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent, in the UK in 2006 by Russia led to widespread outrage and subsequent sanctions. The brutal killing of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist in exile in the US, in 2018 prompted Joe Biden to label Saudi Arabia a pariah. However, he was seen engaging with Muhammad bin Salman, the Saudi crown prince and de facto leader, the following year, indicating a nuanced approach to diplomatic relations. India, meanwhile, denies any role in Nijjar’s assassination and might escape severe repercussions. The inconsistencies in dealing with such incidents reveal the enduring ethical and legal dilemmas surrounding state-backed assassinations.

Historical texts and literature have depicted varying perspectives on assassinations. The Bible praises Ehud, an Israelite, for killing Eglon, the oppressive Moabite king, while also advocating obedience to authority. Assassination, defined as the unlawful killing of a prominent individual for political reasons, is often associated with treachery. Dante, in his Divine Comedy, condemned the assassins of Julius Caesar to the deepest circles of Hell. However, states continue to eliminate adversaries abroad for various reasons and employing diverse methods. A 2016 study by Warner Schilling and Jonathan Schilling outlined 14 potential motives, ranging from revenge to undermining an enemy or destabilizing a rival state.

Accurate data on assassination patterns and their motivations are scarce due to the challenges in attributing responsibility. According to a study by Benjamin Jones and Benjamin Olken in the American Economic Journal in 2009, 298 attempts on national leaders were recorded between 1875 and 2004. Since 1950, an assassination of a national leader has occurred almost every other year.

Rory Cormac, from the University of Nottingham, sees the incident in Canada as indicative of the eroding international norms against assassination. He identifies two contributing factors: the increasing boldness of authoritarian regimes in challenging liberal norms and the democracies’ turn to targeted killings, which has empowered other states. Additional elements, such as improved mobility and drone technology enabling long-range surveillance and attacks, likely exacerbate the issue. Over the years, the US has utilized drones to eliminate thousands of suspected jihadists, along with numerous civilians.

While assassinations may not have historically altered the course of world events, as noted by British politician Benjamin Disraeli, certain killings have had profound consequences. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 by a Serbian nationalist sparked World War I. Assassinations also carry the risk of retaliation, as evidenced by alleged Iranian plots against former American officials Mike Pompeo and John Bolton. In the UK, MI5 has reported Iranian intentions to abduct or kill individuals perceived as enemies of the regime.

Different nations have preferred methods for carrying out assassinations. Russia is known for using poison, as seen in the cases of Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal. North Korea also used a nerve agent to kill Kim Jong Nam in 2017. In contrast, America favors more direct methods, such as the raid that killed Osama bin Laden in 2011 and drone strikes that eliminated Ayman al-Zawahiri and Qassem Suleimani.

Despite President John F. Kennedy’s disapproval of assassinations in 1961, the US has a history of involvement in such activities, targeting figures like Fidel Castro and Rafael Trujillo. This led to a backlash and the issuance of an executive order in 1976 by President Gerald Ford, prohibiting American government members from engaging in assassinations. However, killings abroad persist, with democracies like the US seeking to frame them as “targeted killings” under a veneer of legal justification, especially against suspected terrorists.

The UN Charter mandates member states to refrain from using force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state while recognizing the right to self-defense. International human rights lawyers generally view assassinations and targeted killings as unlawful in peacetime, with exceptions during wartime based on compliance with the laws of war. The legal approach to international terrorism, which falls between ordinary policing and war, is debated, but Mary Ellen O’Connell of the University of Notre Dame argues for addressing terrorism through law enforcement tools, labeling lethal action as “extra-judicial killing.”

The US, however, has sought to expand its legal latitude. It has argued for military action where a state is unable or unwilling to prevent terrorism and designated certain territories as “areas of active hostilities.” The right to self-defense has also been extended to include responding to attacks by non-state actors and to allow for “anticipatory self-defense” against imminent threats. These interpretations have been stretched and redefined over the years, with the Bush and Obama administrations adopting ideas of pre-emption and redefining the concept of “imminence.”

This American stance has influenced similar shifts in the UK, Australia, and France, according to Luca Trenta of Swansea University. However, Professor O’Connell contends that this represents the West granting itself privileges not applicable to others, violating international law. India might argue that Nijjar’s killing aligns with Western counter-terrorism principles, citing historical instances of Sikh separatism leading to violence. The Indian government denies involvement in Nijjar’s death and criticizes the West’s reluctance to address Sikh separatists. As India continues to erode democratic freedoms, cooperation in law enforcement becomes increasingly challenging.

Developing capabilities for covert operations is a complex task, requiring resources and expertise. India’s intelligence agencies might perceive themselves as following the footsteps of their American and Israeli counterparts in defending democracy. Discussions of the “Israelification” of India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) have emerged. However, if RAW shifts from addressing clear security threats to targeting political adversaries, it risks becoming a symbol of domestic repression, akin to the intelligence agencies of Russia and Saudi Arabia. Assassinations serve as stark reminders of the harshness of the regimes that orchestrate them.