A few years ago, amid California’s escalating wildfire seasons, Nat Friedman endured the loss of his family home to the flames. Subsequently, during the Covid-19 lockdown in the Bay Area, a mixture of anxiety and ennui prompted him to seek solace and wisdom in the annals of ancient Rome. While many found distraction in popular culture like “Tiger King” and children’s toys, Friedman delved into books on the empire and collaborated with his daughter to craft paper models of Roman villas. In lieu of mastering sourdough, he honed his skills in baking Panis Quadratus, a Roman bread depicted in Pompeii’s frescoes. Amid sleepless nights, he delved deep into online realms, stumbling upon the enigmatic Herculaneum papyri—a discovery that ignited a consuming fascination. He recalls his astonishment: “How has no one ever told me about this?”

The Herculaneum papyri comprise a trove of scrolls steeped in near-mythical allure for classicists. These scrolls, entombed within an Italian countryside villa, were ensnared by the same volcanic eruption in 79 A.D. that enshrined Pompeii in time’s grasp. Only a fraction of the villa has been excavated, yielding around 800 scrolls thus far. Yet, scholars speculate that the villa, believed to belong to Julius Caesar’s affluent father-in-law, may harbor thousands, if not tens of thousands, more texts. If unearthed, this cache would constitute the largest compendium of ancient texts ever discovered, potentially enriching our understanding of Greek and Roman poetry, drama, and philosophy manifold. Among scholars’ fervent desires lie the works of luminaries such as Aeschylus, Sappho, and Sophocles, while the prospect of uncovering insights into Christianity’s nascent years tantalizes the imagination.

“Some of these texts could revolutionize our understanding of pivotal epochs in ancient history,” asserts Robert Fowler, a classicist and the Herculaneum Society’s chair—an organization dedicated to promoting awareness of the scrolls and the villa site. “This is the society that laid the groundwork for the modern Western world.”

Friedman (right) and Brent Seales, who’s been working to read the scrolls for 20 years. Photographer: Helynn Ospina for Bloomberg Businessweek

The enigmatic contents of the Herculaneum papyri remain veiled due to the capricious fury of Mount Vesuvius. Preserved by scorching mud and debris, the scrolls suffered the ignominious fate of being charred beyond recognition by the volcanic inferno. Despite centuries of concerted efforts to unfurl them, the scrolls resemble charred logs salvaged from an extinguished campfire, their brittle nature defying attempts at unraveling without crumbling into ashy remnants.

In recent times, endeavors have focused on generating high-resolution 3D scans of the scrolls, aiming to virtually unveil their secrets. However, progress has been tantalizingly slow, with scholars only glimpsing fragments of the scrolls’ interiors and faint traces of ink on the papyrus. Although some experts claimed to discern letters in the scans, consensus remained elusive, and the logistical challenges of scanning the entire collection posed formidable obstacles, rendering the endeavor financially prohibitive for all but the wealthiest benefactors. The deciphering of words or paragraphs has remained an enduring enigma.

Enter Nat Friedman, not your typical aficionado of ancient Rome but the former CEO of GitHub Inc., a renowned software development platform acquired by Microsoft Corp. in 2018. With firsthand insight into the burgeoning potential of artificial intelligence (AI), Friedman harbored a bold notion that AI algorithms could discern patterns in the scroll images evading human perception.

After meticulous deliberation and engagement with the classics community, Friedman, now an AI-focused investor after departing GitHub, initiated the Vesuvius Challenge. This groundbreaking contest, launched last year, offered $1 million in prizes to individuals capable of developing AI software capable of deciphering passages from a single scroll. “Maybe there were obvious strategies no one had considered,” Friedman mused, drawing from his extensive entrepreneurial experiences.

Months passed, and Friedman’s intuition proved prescient. Contestants worldwide, predominantly young computer scientists, devised innovative techniques to process the 3D scans, transforming them into decipherable sheets. Some even discerned letters and subsequently words, fostering vibrant discussions on Discord while receiving occasional scrutiny or admiration from seasoned classicists.

On February 5th, Friedman and his academic collaborator, Brent Seales, a computer science professor and scroll expert, plan to unveil the remarkable progress achieved by a group of contestants, who have transcribed numerous passages from one of the scrolls. While cautioning against premature conclusions, Friedman expresses unwavering confidence that these techniques will unlock the scrolls’ complete contents. “My ambition,” he asserts, “is to unveil their entirety.”

An artist’s rendering of the villa where the scrolls were found. Source: Rocío Espín

Prior to the cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, Herculaneum nestled serenely on the shores of the Gulf of Naples, serving as a tranquil retreat for affluent Romans seeking reprieve. Unlike its ill-fated counterpart Pompeii, which bore the brunt of Vesuvian fury directly, Herculaneum endured a gradual entombment beneath layers of ash, pumice, and noxious gases. Though hardly gentle, this process afforded most residents the opportunity to flee, leaving much of the town preserved beneath the solidifying igneous mantle. The town’s rediscovery in the 18th century, initiated by farmers unearthing marble statues, offered glimpses into its storied past. Among the notable discoveries was the villa presumed to have belonged to Senator Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, known colloquially as Piso, the father-in-law of Caesar.

During this period of excavation, early pioneers tunneled into the villa primarily in pursuit of conspicuously valuable artifacts such as statues, paintings, and recognizable household items. Initially, the scrolls, often strewn across the vibrant floor mosaics, were mistaken for mere logs and discarded, only to be recognized later as charred papyrus fragments commonly found within libraries or reading chambers. Attempts to unfurl the scrolls, however, proved disastrous, with various misguided methods including the application of mercury and the exposure to noxious gases inflicting irreparable harm.

Some scrolls endured the indignity of being sliced, excavated, and otherwise maltreated, evoking sorrow from historians witnessing their desecration.

One notable endeavor during this era was led by Antonio Piaggio, a priest, who ingeniously constructed a wooden rack equipped with silken threads designed to delicately unfurl the scrolls at a painstaking rate of one inch per day. While yielding some measure of success, Piaggio’s contraption often resulted in damage or fragmentation of the scrolls. Subsequent centuries witnessed the efforts of European teams, including a contingent assembled under Napoleon’s auspices, painstakingly piecing together fragments of mostly illegible text in a bid to reconstruct the scrolls’ narratives.

Today, the villa remains largely concealed, its treasures unexplored and inaccessible even to seasoned experts. Much of the decipherable content discovered thus far has been attributed to Philodemus, an Epicurean philosopher and poet, leading scholars to speculate about the existence of a larger main library concealed elsewhere on the premises. Given the erudition and affluence of a figure like Piso, historians envision a repository stocked with classical literature, modern historical treatises, legal doctrines, and philosophical works. Richard Janko, a professor of classical studies at the University of Michigan, who has meticulously reconstructed scroll fragments, believes in the presence of a vast library awaiting discovery.

“I see no reason to think it should not still be there and preserved in the same way,” he remarks, emphasizing the potential magnitude of the collection, which could rival those of ordinary citizens from antiquity who possessed tens of thousands of scrolls. Piso’s correspondence with Cicero and the apostle Paul’s visit to the region before Vesuvius erupted further kindle speculation about the potential literary treasures buried within the villa. Despite the recovery of approximately 800 scrolls to date, Janko conjectures that thousands, if not tens of thousands, more lie concealed within its depths.

In the realm of modern scholarship, Brent Seales, a computer science professor at the University of Kentucky, stands as a pioneering figure in the quest to unlock the secrets of the scrolls. For two decades, Seales has leveraged advanced medical imaging technology, originally designed for CT scans and ultrasounds, to decipher ancient texts deemed unreadable. Throughout this period, the Herculaneum papyri have remained a primary focus of his endeavors. “I had to,” he reflects, “No one else was working on it, and no one really thought it was even possible.”

Progress was gradual. Seales developed software theoretically capable of virtually unrolling coiled scrolls; however, when tested on a genuine Herculaneum scroll in 2009, it faltered under the complexity of the task. “The layers inside the scroll were not uniform. They were all tangled and mashed together, and my software could not follow them reliably,” Seales recalls.

By 2016, Seales and his team successfully deciphered the Ein Gedi scroll, an ancient Hebrew text, by adapting their software to detect variations in density between the charred manuscript and the ink layered upon it. Despite this breakthrough, the carbon-based ink used in the Herculaneum papyri posed a fresh challenge beyond their imaging capabilities.

In recent years, Seales has turned to artificial intelligence (AI) for assistance. His team employed more advanced imaging equipment and trained algorithms to discern patterns in visible ink portions of the papyrus. The AI’s capacity to detect nuances beyond human perception offered promising prospects, yet significant obstacles persisted. While the technology unveiled fragments of the scrolls, the majority remained indecipherable, necessitating further innovation.

Running tiny scroll fragments through a particle accelerator yielded valuable training data for contestants’ AI models. Courtesy: Vesuvius Challenge

In 2020, Friedman began closely tracking Seales and the Herculaneum papyri, propelled by his burgeoning fascination with ancient Rome. After a year passed without developments, he delved into YouTube videos where Seales outlined the hurdles hindering progress. Chief among these challenges was funding. By 2022, Friedman was convinced he could make a difference. Inviting Seales to California for an event attended by Silicon Valley luminaries, Seales presented the scrolls, but the response fell short. “I felt very, very guilty about this and embarrassed because he’d come out to California, and California had failed him,” Friedman recalls.

In a spontaneous move, Friedman proposed a contest to Seales, offering to contribute his own funds, matched by his investing partner Daniel Gross. Seales wrestled with the implications. The Herculaneum papyri had become his life’s work, and he aspired to decode them himself. Moreover, several of his students had invested considerable time and effort in the project, intending to publish papers on their findings. Suddenly, Silicon Valley tycoons were encroaching on their domain, suggesting that online enthusiasts could achieve breakthroughs that had eluded seasoned scholars.

Beyond personal acclaim, Seales harbored a genuine desire for the scrolls to be deciphered and agreed to explore Friedman’s proposal. Together, they launched the Vesuvius Challenge on the Ides of March, garnering support from Friedman’s tech contacts, who pledged financial contributions. As the initiative gained momentum, a team of aspiring papyrologists embarked on the daunting task ahead. Within days, Friedman amassed sufficient funds to offer $1 million in prizes, along with additional resources to facilitate essential groundwork.

Friedman enlisted individuals online to collate existing scroll imagery, organize it, and develop software tools for segmenting and flattening the images for digital readability. Recognizing the transformation of his hobby into a full-fledged endeavor, Friedman compensated select team members generously, paying them $40 per hour.

The initial buzz generated by the contest opened new avenues. Seales had spent years persuading Italian and British collectors to scan his initial scrolls. With Friedman’s backing, Italian authorities offered two new scrolls for scanning, prompting the team to develop precision-fitting 3D-printed cases for their safe transportation to a particle accelerator in England. There, over three intense days, the scrolls underwent high-resolution scanning at a cost of approximately $70,000.

Observing the imaging process firsthand underscored both its enchantment and complexity. The scanner scrutinized minute scroll remnants, capturing them with high-energy X-rays akin to a human undergoing a CT scan. The resulting images, delivered in ultra-high resolution (about 8 micrometers), revealed infinitesimal changes in density and thickness along each slice. Software was then employed to unfurl and flatten the slices, unveiling recognizable papyrus sheets with concealed writing.

Given the cumbersome file sizes and computational challenges, Friedman stipulated that contestants vying for the $700,000 grand prize must decipher just four passages of at least 140 contiguous characters by the end of 2023. Along the journey, smaller prizes ranging from $1,000 to $100,000 would be awarded for various achievements, such as the first successful reading of letters in a scroll or the development of software tools enhancing image processing. Committed to open-source principles, Friedman mandated that contestants reveal their methodologies to the public.

Among those captivated by the contest was Luke Farritor, a spirited 22-year-old undergraduate from Nebraska. Inspired by Friedman’s podcast interview, Farritor envisioned the opportunity as his own. The initial stages were marked by arduous attempts to decipher blurred images. However, Casey Handmer, an Australian mathematician and physicist, made a pivotal breakthrough by discerning a subtle pattern dubbed “crackle” on the page, resembling dried-out ink lifted from the surface—a discovery that signaled a significant advance in the quest to unravel the scrolls’ secrets.

Farritor in his basement with his heavy-duty computer and his results. Photographer: Shawn Brackbill for Bloomberg Businessweek

Handmer’s crackle revelation prompted him to explore the presence of letter fragments in a scroll image. Embracing the collaborative ethos of the contest, he shared his breakthrough on the Vesuvius Challenge’s Discord channel in June. Farritor, then a summer intern at SpaceX, stumbled upon the post while enjoying a break in the company break room. His initial incredulity soon gave way to intrigue. Over the following month, he meticulously scoured other image files for traces of crackle, identifying isolated letters hidden within the patterns. While most letters eluded human detection, approximately 1% to 2% exhibited discernible crackle. Leveraging these scant clues, Farritor trained a model to detect obscured ink, gradually unveiling additional letters. He systematically incorporated these newfound letters into the model’s training dataset, refining its capacity to discern hidden text through successive iterations. The model’s iterative learning process commenced with the crackle pattern, initially visible only to the human eye, and progressively acquired the ability to perceive imperceptible ink traces.

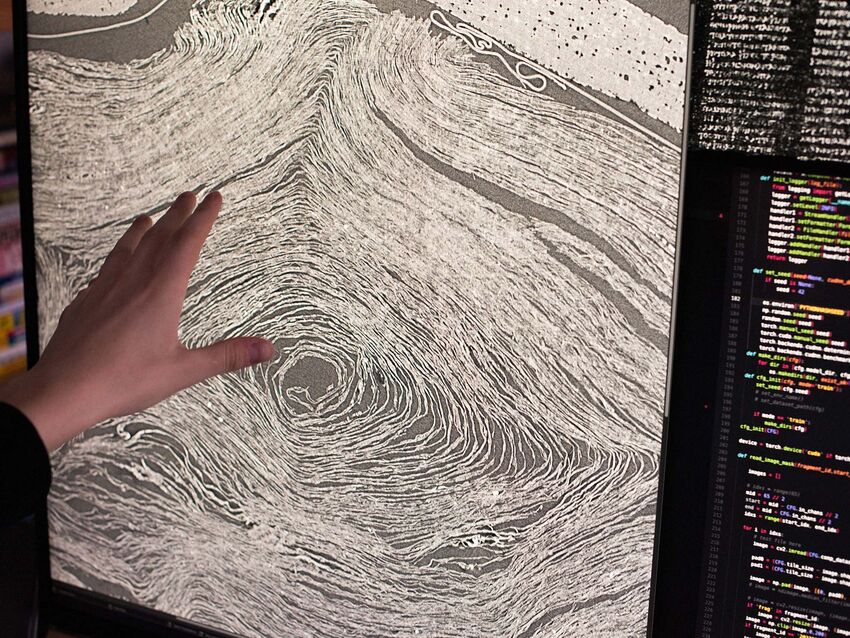

A cross-section scan of a scroll on Farritor’s screen. Photographer: Shawn Brackbill for Bloomberg Businessweek

In contrast to the data-intensive nature of today’s large-language AI models, Farritor’s model thrived on minimal inputs. It simply evaluated each 64-pixel-by-64-pixel segment of the image, asking a straightforward question: is there ink present or not? The structured layout of Greek letters, aligned with the cross-hatched papyrus fibers, facilitated the model’s task.

In early August, Farritor seized an opportunity to put his software through its paces. Back in Nebraska for the remainder of the summer, he found himself at a lively house party with friends when a new image, rich with crackle patterns, appeared on the contest’s Discord channel. Amidst the revelry, Farritor remotely accessed his dorm computer from his phone, swiftly processed the image through his machine-learning system, and set his phone aside. “An hour later, after seeing off my inebriated friends, I checked my phone not expecting much,” he recalls. “To my surprise, three Greek letters gleamed on the screen.”

Around 2 a.m., Farritor shared his discovery with his mom, Friedman, and fellow contestants, his excitement barely contained. “That was the moment I realized, ‘Wow, this is actually happening. We’re going to decipher the scrolls,'” he reflects.

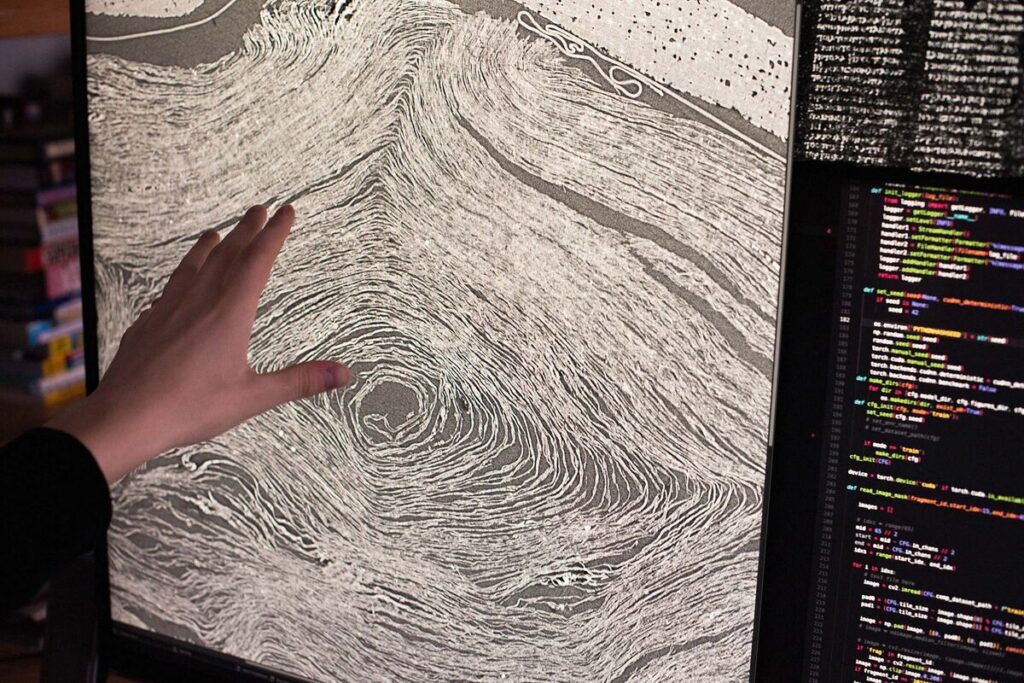

Before long, Farritor uncovered ten letters, earning a $40,000 prize for his significant progress. Expert evaluations confirmed that he had identified the Greek word for “purple.”

Undeterred, Farritor persisted in refining his machine-learning model using crackle data, documenting his advances on Discord and Twitter. His breakthroughs, alongside Handmer’s, ignited renewed fervor among contestants, inspiring others to adopt similar methodologies. In late 2023, Farritor forged an alliance with two fellow contestants, Youssef Nader and Julian Schilliger, pooling their technologies and committing to share any prize winnings.

Farritor’s first win came from identifying the word “ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ” (“purple”) on the center line here. Courtesy: Vesuvius Challenge

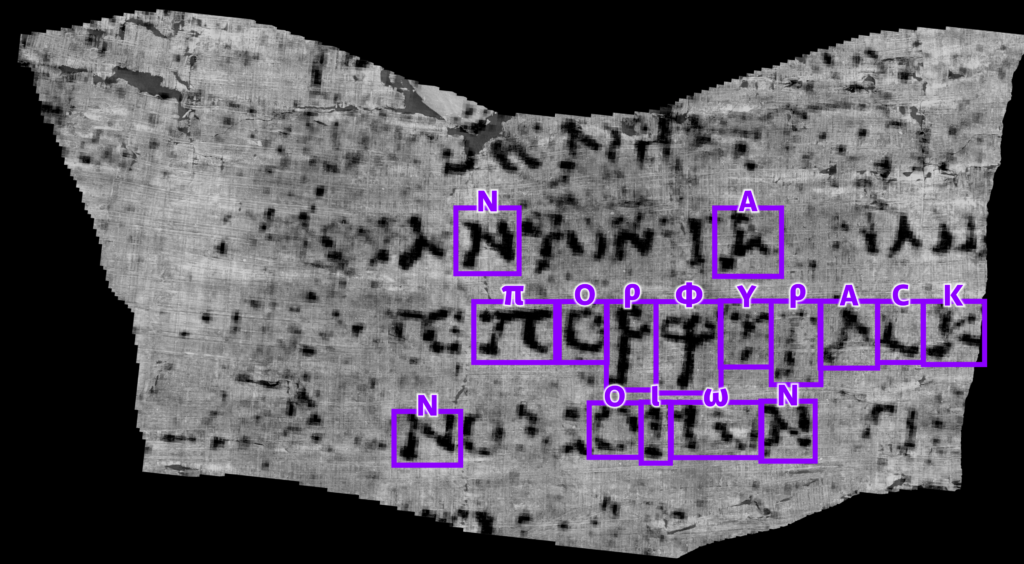

Ultimately, the Vesuvius Challenge attracted 18 entries vying for its grand prize. While some submissions fell short of expectations, a select few validated Friedman’s bold venture. What were once enigmatic blurs in the scroll images now illuminated entire paragraphs of letters, courtesy of the AI systems. The past was brought vividly to life. “It’s a situation that you practically never encounter as a classicist,” remarks Tobias Reinhardt, a professor of ancient philosophy and Latin literature at the University of Oxford. “You mostly look at texts that have been looked at by someone before. The idea that you are reading a text that was last unrolled on someone’s desk 1,900 years ago is unbelievable.”

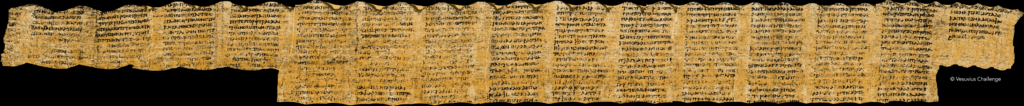

The winning entry from Farritor, Nader and Schilliger shows text across 15 columns of one of the scrolls. Courtesy: Vesuvius Challenge

A panel of classicists meticulously reviewed all the entries and unanimously declared Farritor’s team as the winners. Their submission seamlessly stitched together over a dozen columns of text, featuring entire paragraphs scattered throughout.

While the scholars are still translating, they believe the text to be another masterpiece by Philodemus, focusing on the pleasures of music, food, and their impact on the senses. “Peering at and beginning to transcribe the first reasonably legible scans of this brand-new ancient book was an extraordinarily emotional experience,” expresses Janko, one of the reviewers. While these passages may not unveil profound insights into ancient Rome, most classics scholars hold out hope for what may emerge next.

There exists the possibility that the villa has exhausted its treasures—that there are no more extensive libraries with thousands of scrolls awaiting discovery—or that the remaining scrolls offer nothing groundbreaking. However, there’s also the potential that they contain valuable lessons applicable to the modern world.

In the modern landscape lies Ercolano, a town of approximately 50,000 residents erected atop ancient Herculaneum. Many inhabitants own property and buildings situated atop the villa site. “They would have to displace people from Ercolano and demolish everything to unearth the ancient city,” remarks Federica Nicolardi, a papyrologist at the University of Naples Federico II.

Short of a large-scale relocation, Friedman is dedicated to refining the current findings. The initial contest yielded only about 5% of one scroll, leaving much yet to be explored. He envisions a new cohort of contestants potentially reaching up to 85%. Additionally, he aims to fund the development of automated systems to accelerate the processes of scanning and digital refinement. Contemplating his next steps, Friedman considers investing in scanners placed directly at the villa, capable of scanning numerous scrolls daily. “Even if there’s just one dialogue of Aristotle or a beautiful lost Homeric poem or a dispatch from a Roman general about this Jesus Christ guy who’s roaming around,” he reflects, “all you need is one of those for the whole thing to be more than worth it.”